Chapter 1: Getting Started With ETFs

Introduction

If I could go back and give my 25-year-old self one piece of financial advice, it would be this: "Stop trying to pick individual stocks and just buy index ETFs." That single decision would have saved me years of stress, countless hours of research, and most importantly, hundreds of thousands of dollars in missed returns.

Fifteen years ago, I was convinced I could beat the market. I had spreadsheets tracking P/E ratios, spent weekends reading annual reports, scrolling hundreds of chart daily, and thought I was smarter than the "dumb money" buying index funds. I was wrong. Dead wrong.

This chapter is the foundation of everything that follows—why ETFs work, how they're structured, and most importantly, why they consistently outperform the stock-picking strategies that cost me so much time and money early in my investing career.

What Is an ETF?

An Exchange-Traded Fund (ETF) is a basket of securities—stocks, bonds, or other assets—that trades on an exchange just like an individual stock. Think of it as buying a slice of an entire market rather than betting on individual companies.

When I buy one share of VTI (Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF), I instantly own a piece of over 3,500 US listed companies. From Apple and Microsoft down to tiny regional banks and niche manufacturers I've never heard of. It's like buying the entire stock market in a single transaction.

Here's what makes ETFs special:

Instant Diversification: Instead of researching and buying 20 individual stocks to create a diversified portfolio, I can achieve better diversification with a single ETF purchase. VTI gives me exposure to large-cap growth stocks, small-cap value companies, REITs, and everything in between.

Professional Management: While ETFs are "passively managed," they're not unmanaged. Fund companies like Vanguard and BlackRock employ teams of professionals to handle the complex logistics—corporate actions, dividend reinvestment, tax optimisation, and rebalancing—that would be impossible for individual investors to manage efficiently.

Transparency: I know exactly what I own. ETF holdings are published daily, unlike mutual funds that only disclose positions quarterly. If I want to see VTI's top 10 holdings right now, that information is freely available.

Liquidity: ETFs trade throughout market hours at market prices. If I need to sell my position, I can do it instantly during any trading session, not just at the end-of-day price like mutual funds.

Lower Costs: The average ETF expense ratio is 0.20%, compared to 1.40% for actively managed mutual funds. That difference might seem small, but over decades, it's the difference between a comfortable retirement and working into your 70s.

When people ask me to explain ETFs in simple terms, I use this analogy:

Imagine you want to own a piece of every restaurant in your city, but you don't want to negotiate with hundreds of individual restaurant owners. An ETF is like a company that buys stakes in all the restaurants, then sells you shares of that company. You get exposure to the entire restaurant industry without the complexity of individual negotiations.

That's exactly what VTI does for the U.S. stock market, SPY does for large-cap stocks, and QQQ does for the most popular tech stocks. Simple, efficient, and incredibly effective.

How ETFs Work

The mechanics of how ETFs work might seem complex, but understanding the basics helps explain why they're so efficient. You don't need to become an expert, but knowing the fundamentals will make you a more confident ETF investor.

The Creation Process:

Large financial institutions called "Authorised Participants" (APs) create new ETF shares by delivering a basket of underlying securities to the ETF provider. For example, to create new shares of SPY, an AP would deliver the exact mix of stocks that make up the S&P 500 to State Street (SPY's provider). In return, they receive newly created SPY shares.

This happens in large blocks—typically 50,000 shares at a time called "creation units." The AP can then sell these ETF shares on the open market to investors like you and me.

The Redemption Process:

The process works in reverse when there's more selling pressure than buying pressure. APs can return large blocks of ETF shares to the fund company and receive the underlying securities back. This keeps supply and demand in balance and prevents ETF prices from deviating significantly from their net asset value (NAV).

Why This Matters for Individual Investors:

This creation/redemption mechanism provides two massive benefits:

Price Efficiency: ETF prices stay very close to the value of their underlying holdings. Unlike closed-end funds, which can trade at significant premiums or discounts to NAV, ETFs rarely deviate more than a few cents from fair value.

Liquidity: Even if an ETF doesn't have high trading volume, the creation/redemption process ensures you can always buy or sell at fair prices. The liquidity comes from the underlying securities, not just other ETF traders.

Real-World Example:

Let's say SPY is trading at $500 per share, but the underlying S&P 500 stocks are worth $500.50 per share. This creates an arbitrage opportunity. An AP can:

Buy the 500 individual S&P 500 stocks for $500.50

Exchange them for SPY shares

Sell the SPY shares for $500

Pocket the $0.50 difference (minus transaction costs)

This arbitrage activity happens automatically and keeps ETF prices aligned with their underlying assets. As an individual investor, you benefit from this institutional activity without having to understand or participate in it directly.

The beauty of this system is that it works without any intervention from you. You simply buy ETF shares through your broker just like buying individual stocks, but behind the scenes, this sophisticated mechanism ensures you're always getting fair value.

Why ETFs Beat Picking Individual Stocks

This section represents the most expensive lesson of my investing career. From 2015 to 2020, I was convinced I could outperform the market through careful stock selection. I had a system, did my research, and felt confident in my abilities. The results were humbling.

The Academic Evidence:

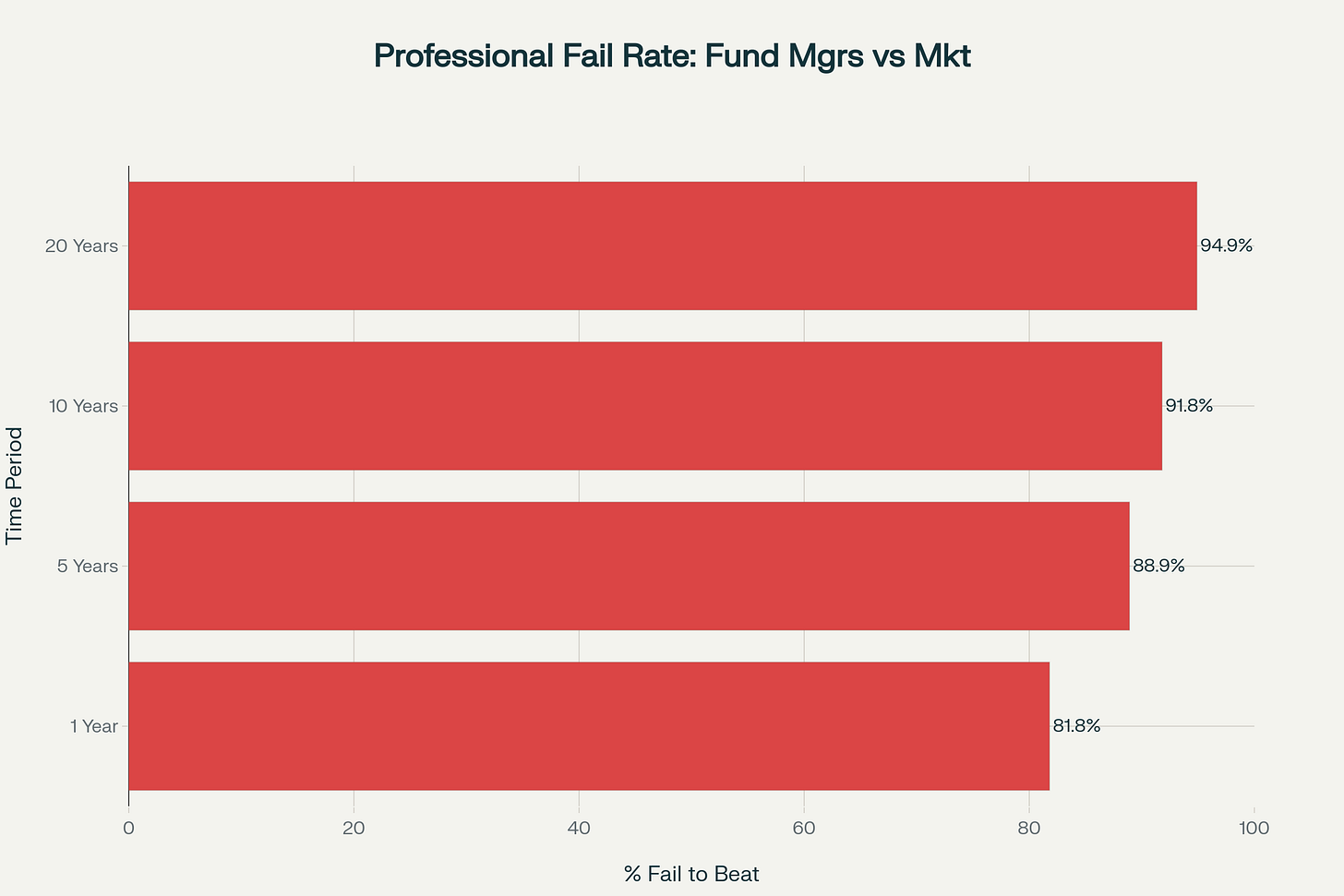

Before sharing my personal experience, let's look at the data. The SPIVA (S&P Indices Versus Active) scorecard tracks how professional fund managers perform against their benchmarks. These are people with MBA degrees, CFA qualifications, research teams, and direct access to company management. If anyone should be able to beat the market, it's them.

The results? In 2024, only 18.2% of large-cap active funds outperformed the S&P 500. Over 10 years, that number drops to just 8.2%. Over 20 years? A dismal 5.1%.

Think about that: Professional investors with unlimited resources, research teams, and decades of experience have a 95% failure rate over 20 years. What made me think I could do better from my laptop?

My Personal Stock-Picking Experiment:

In January 2015, I decided to put my stock-picking skills to the test. I split $10,000 into two equal buckets:

$5,000 into SPY (S&P 500 ETF)

$5,000 into my "best ideas" stock portfolio

My stock portfolio consisted of what I thought were slam-dunk picks:

Tesla (TSLA) - 15%: Electric vehicles were the future

Netflix (NFLX) - 15%: Streaming would kill cable TV

Amazon (AMZN) - 20%: E-commerce dominance

Apple (AAPL) - 15%: iPhone super-cycle

Microsoft (MSFT) - 10%: Cloud computing growth

Google (GOOGL) - 15%: Search and advertising monopoly

Looking at this list now, you might think, "Those are all great companies! How could you lose?" That's exactly the problem with stock picking—even when you're right about the companies, you can still be wrong about the timing, valuation, or market sentiment.

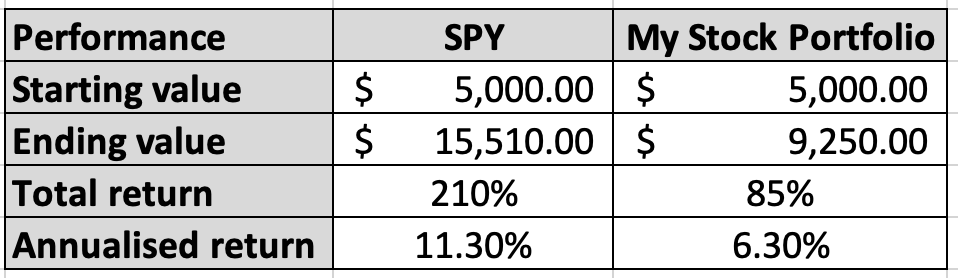

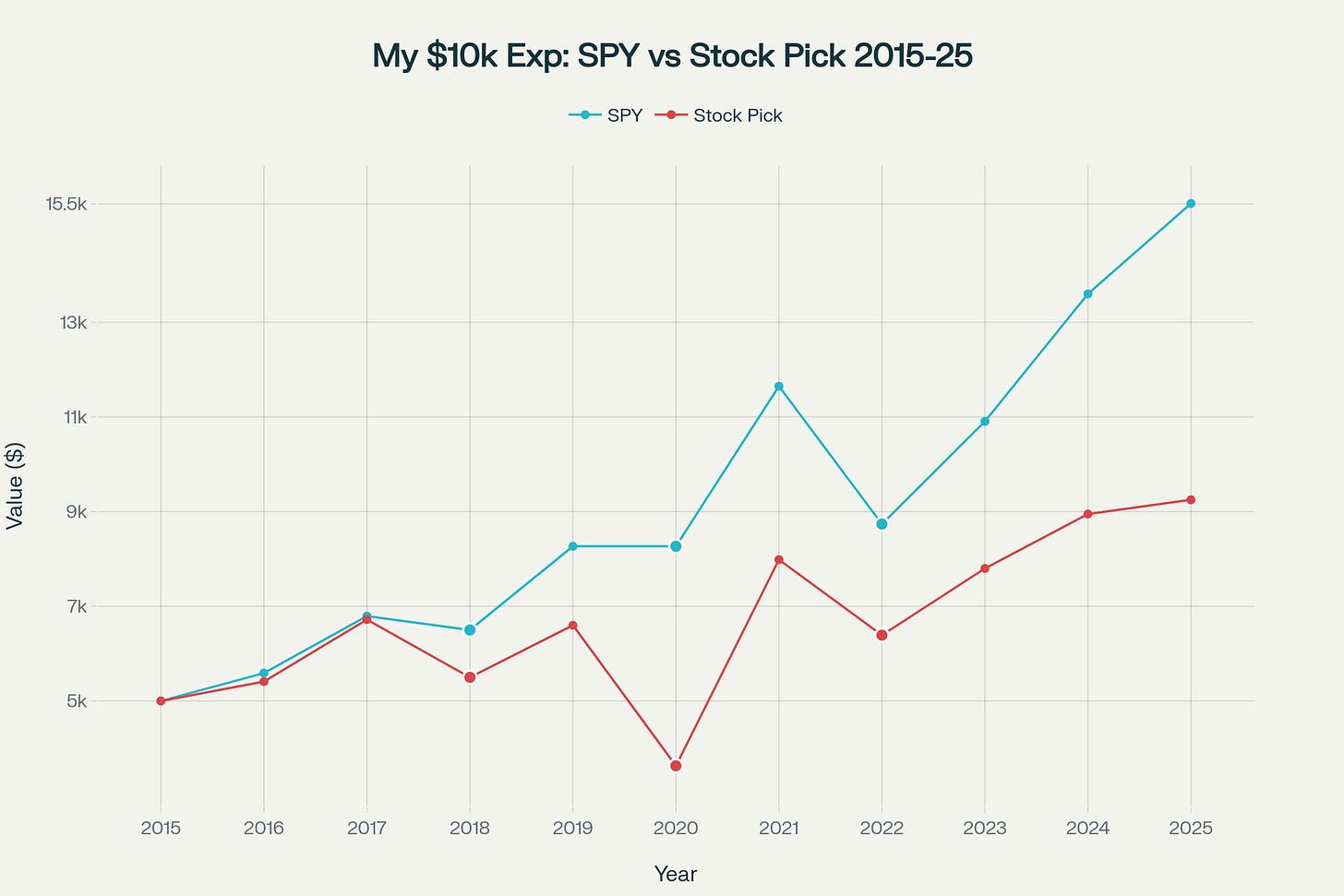

The Results (January 2015 - January 2025):

The SPY investment more than tripled while my carefully researched stock picks less than doubled. Even worse, my portfolio experienced much higher volatility. During the March 2020 COVID crash, my stocks fell 45% while SPY dropped 30%. The stress was unbearable.

Why Did I Underperform?

Looking back, I made several classic mistakes:

Timing Errors: I bought Tesla at $250 in 2015, watched it go to $400, got scared of the valuation, and sold. It later hit $1,200+ (pre-split). I was right about the company but wrong about my entry and exit points.

Overconfidence: After Tesla's early gains, I thought I was a genius. I increased my position sizes and took bigger risks. Overconfidence kills returns.

Emotional Trading: When Netflix dropped 15% after a disappointing subscriber report, I panic-sold, convinced the streaming story was over. It recovered within months.

Concentration Risk: Despite owning several stocks, they were all growth companies that moved together. When growth was out of favor in 2018, my entire portfolio suffered.

High Turnover: I was constantly "optimizing" my portfolio, selling winners too early and holding losers too long. Each trade incurred costs and triggered taxes.

Anchoring Bias: I fell in love with my picks and held onto losing positions too long, hoping they'd recover.

Information Overload: I spent hours reading analyst reports, earnings transcripts, and market commentary. Instead of making me a better investor, the constant information flow made me more reactive and prone to second-guessing.

The Diversification Math:

Even if I had picked all winners, concentration risk would have limited my upside. With only seven positions, any single stock disaster could devastate my portfolio. SPY's 500+ holdings provided natural protection against company-specific risks.

Consider this: During my experiment period, several major companies had catastrophic declines:

General Electric fell 80%

Wells Fargo dropped 60%

Boeing declined 65% (before recovering)

If any of these had been 15-20% positions in my portfolio, it would have been devastating. SPY holders barely felt these individual company problems because they were tiny parts of a massive, diversified portfolio.

The Behavioural Challenge:

Perhaps the biggest advantage of ETF investing is that it removes the behavioral challenges that destroy individual stock investors:

No more agonising over earnings reports

No more second-guessing buy/sell decisions

No more staying up late reading analyst upgrades and downgrades

No more FOMO when other stocks are performing better

No more analysis paralysis when choosing between competing investments

When I own VTI, I own everything. I don't have to worry about whether Amazon will beat Netflix, or whether Microsoft will outperform Apple. I own them all, and the market decides the winners.

Wisdom from the greatest investor of all time

Even Warren Buffett, arguably the greatest stock picker in history, recommends index funds for ordinary investors. In his 2013 shareholder letter, he wrote: "My advice to the trustee couldn't be more simple: Put 10% of the cash in short-term government bonds and 90% in a very low-cost S&P 500 index fund."

If Buffett recommends indexing for his own wife's inheritance, that should tell you something about the difficulty of beating the market through stock selection.

The math is clear, the academic evidence is overwhelming, and my personal experience confirms it: for the vast majority of investors, ETFs provide better returns with less stress, lower costs, and greater tax efficiency than stock picking.

The question isn't whether you can beat the market by picking individual stocks—it's whether you can beat the market consistently, after transaction costs, while maintaining your sanity and not getting wiped out by inevitable mistakes.

For me, the answer was a resounding no. ETFs solved all these problems while delivering superior returns with a fraction of the time and stress.

During the October 2018 correction, I made my first major mistake.

Mistake #1: Emotional Selling (October 2018)

When Netflix reported slower subscriber growth, the stock dropped 15% in a single day. Suddenly, my "cord-cutting" thesis seemed naive. What if Disney+ killed Netflix? What if content costs spiraled out of control?

I sold my entire Netflix position at $252 per share. The stock hit $690 by 2021 (pre-split). That single emotional decision cost me thousands in returns.

Mistake #2: Overconfidence Bias (2019)

After Netflix burned me, I became convinced I could time my other positions better. I sold half my Tesla position at $380 per share in August 2019, thinking it was "obviously overvalued."

Tesla proceeded to hit $1,794 by January 2021 (pre-split). My "smart" selling cost me even more.

Mistake #3: FOMO Buying (2020)

During the March 2020 COVID crash, I watched my remaining positions fall 45% while SPY "only" dropped 30%. But instead of staying disciplined, I got caught up in the recovery narrative.

I used the cash from my Netflix and Tesla sales to buy Zoom at $385 per share, convinced that video conferencing was the new normal. Zoom peaked at $588, then crashed to $70 as the world reopened. Another painful lesson in trend-chasing.

The Hidden Costs:

The performance gap was actually worse than these numbers suggest because I didn't account for:

Trading commissions: $7 per trade x 37 trades = $259

Bid-ask spreads: Estimated $150 in total costs

Opportunity cost: 400 hours at my $50/hour billing rate = $20,000

If I'd spent those 400 hours working billable client projects instead of researching stocks, I could have earned enough to make my total return competitive with SPY. But that's not how psychology works—the time felt "free" because I enjoyed the research.

Behavioural Lessons Learned:

Overconfidence After Early Success: My initial outperformance made me cocky and prone to bigger risks.

Loss Aversion: I held losing positions too long and sold winners too early, the opposite of optimal strategy.

Confirmation Bias: I sought information that confirmed my existing positions while ignoring contrary evidence.

Anchoring: I became emotionally attached to my original purchase prices and couldn't objectively evaluate new information.

Recency Bias: Recent events (like Netflix's bad quarter) felt more important than long-term trends.

Information Overload: More research didn't make me a better investor—it made me more reactive and prone to second-guessing.

What I Should Have Done:

Looking back, if I'd simply bought VTI instead of SPY, I would have captured slightly broader market exposure for lower fees (0.03% vs 0.095%). If I'd dollar-cost averaged $500 per month into VTI over those 10 years, the results would have been even better due to market timing benefits.

The Stress Factor:

Beyond the financial underperformance, stock picking was emotionally exhausting. I checked my portfolio multiple times daily, lost sleep during earnings seasons, and let market volatility affect my mood and relationships.

Meanwhile, my SPY position required zero mental energy. I bought it, forgot about it, and let it compound for a decade. The peace of mind was worth the superior returns alone.

Why Good Companies Weren't Enough:

All seven of my original stock picks were objectively great companies that delivered solid business results. But stock picking isn't just about identifying good companies—it's about:

Buying them at the right price

Holding them through volatility

Avoiding emotional decisions

Timing entry and exit points perfectly

I failed at all of these despite picking fundamentally strong companies.

My experiment proved that even when you're right about long-term trends (electric vehicles, streaming, cloud computing), execution matters more than analysis. ETFs remove the execution challenge by automatically diversifying across all companies and sectors, rebalancing continuously, and eliminating emotional decision-making.

The best stock picker in my portfolio turned out to be the index—it bought all the winners, held them through volatility, and didn't make any of the emotional mistakes that cost me dearly.

This experience converted me from an active stock picker to a passive index investor. It was an expensive education, but one that saved me from decades of future underperformance.

Key Takeaways

What ETFs Are:

Baskets of securities that trade like individual stocks

Provide instant diversification across hundreds or thousands of companies

Managed by professional fund companies but passively track indices

Combine the best features of mutual funds (diversification) and stocks (liquidity)

Why ETFs Beat Stock Picking:

95% of professional fund managers fail to beat their benchmarks over 20 years

Individual investors face even worse odds due to behavioral biases and higher costs

My personal 10-year experiment: SPY returned 210% vs my stocks' 85%

Concentration risk makes individual stock portfolios unnecessarily volatile

Behavioural Benefits:

Eliminates need to research individual companies

Reduces emotional decision-making and timing mistakes

Provides peace of mind through automatic diversification

Frees up time for more productive activities

Cost Advantages:

Lower expense ratios than actively managed funds

No trading costs from frequent rebalancing

Reduced tax drag from capital gains distributions

Eliminates bid-ask spread costs from frequent trading

Coming Up:

In Chapter 2, we'll explore the mathematical foundation that makes ETF investing so powerful: compound interest and dollar-cost averaging. You'll see exactly how small, consistent investments can grow into life-changing wealth over time.

The transition from stock picking to ETF investing was the single most important decision in my wealth-building journey. Everything that follows builds on this foundation.

Sign up now and get our free REITs’ Numerical Ratings.

Disclaimer: This article constitutes the author’s personal views and is for entertainment and educational purposes only. It is not to be construed as financial advice in any form. Please do your own research and seek advice from a qualified financial advisor. From time to time, I have positions in all or some of the mentioned stocks when publishing this article. This is a disclosure - not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks.